As part of the Community Relations Council Good Relations week HTANI hosted an online workshop on Exploring Controversial Issues with Young People. The workshop was led by Dr Judy Pace of the University of San Francisco and attended by teachers, student teachers and educational administrators. Judy has recently published a book, Hard Questions: Learning to Teach Controversial issues. The latter is based on research work carried out with four teacher educators two from NI, one from the English Midlands and one from the Mid-west of the USA, and their pre-service students.

Judy modelled good practice by first introducing us to ASPIRE as a tool for establishing ground rules for the interaction which was to follow, and then, at intervals creating breakout groups which allowed participants the chance to explore ideas as the presentation progressed.

In the early part of her presentation she explored the nature of controversial issues and benefits of addressing them in the classroom. The issues can be social, cultural and political and frequently controversy is most apparent when these three intersect. They can arise from questions of public policy, from contested interpretations of history or, in divided societies particularly, to disputes concerning community identities and allegiances. Whatever the challenges faced by teachers, Judy strongly advocated the value of young people having the opportunity to encounter controversial material in classrooms. Especially, they:

- Increase students’ access to political knowledge and ideas

- Promote democratic citizenship and understanding of human rights

- Encourage civic engagement

- Contribute to peacebuilding and reconciliation in divided societies.

It is important for teachers to recognise the specific characteristics of controversial issues that make them suitable for classrooms. The issue has to be able to be framed as a significant, open question which lends itself to the application of dialogic pedagogies. It has to offer the exploration of multiple perspectives and allow the weighing of different viewpoints and evidence, enabling students to draw conclusions and then self-position.

Arising from her research findings Judy has constructed Teaching Controversial issues: A Framework for Reflective Practice as a guide for practitioners.

The guide is underpinned by the idea that the teachers she studied engaged in “contained risk-taking”. They were committed to tackling controversial issues with their students but were also aware (and often constrained) by potentially negative responses at classroom, school and community levels. Following up, Judy indicated that she was increasingly drawn to the Stanford History Education Group’s Structured Academic Controversy model which places emphasis on taking students through a stepped and reasoned approach to the consideration of evidence and multiple perspectives.

See: https://sheg.stanford.edu/history-lessons

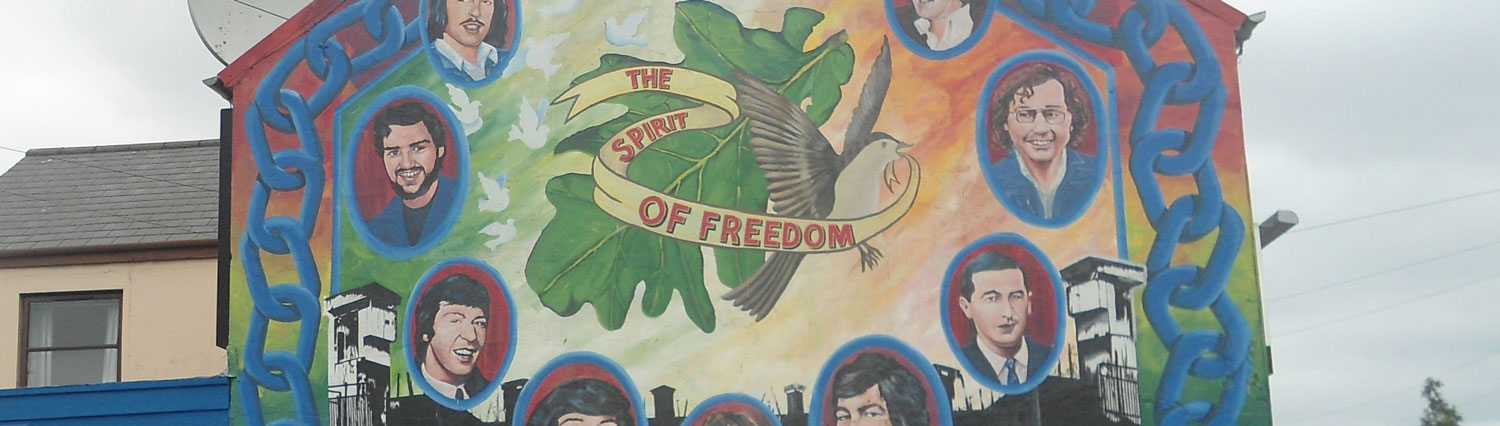

Moving on to discuss her findings specific to Northern Ireland, Judy stressed that the teacher educators and student teachers she observed were committed to creating a better society. They identified with young people who want to (and need to) know about the past and were convinced that the legacy of Northern Ireland’s recent, violent past should be addressed in schools. They wished to help young people better understand how their interpretations of historical issues, particularly, were influenced by seeing them through the lenses shaped by family and community backgrounds. However, applying this in practice they encountered constraints: pressures to cover curriculum content particularly linked to the stress schools placed on examinations, rather than take time to delve into the contemporary ramifications of past events; the low status of citizenship education in schools; and poor student behaviour when they “risked” interactive pedagogies. Further, in the context of largely segregated schools they had anxieties that raising difficult issues might bring negative community responses.

In concluding her presentation Judy posed four questions:

- To what extent should teachers avoid or embrace emotional responses in the classroom?

- Why do NI student teachers have lower expectations than their counterparts in the USA in regard to facilitating sustained discussion amongst young people?

- Why do NI student teachers have lower expectations than their counterparts in the USA in regard to facilitating sustained discussion amongst young people?

- How can we maximise support and minimise constraints on teachers who wish to teach controversial issues?4. What is the optimal “level of constraint” appropriate when teachers engage in risk-taking?

Prior to opening up discussion to all participants HTANI members, Sean Pettis and Alan McCully offered brief comments on Judy’s input.

Sean responded first. For him, teaching controversial issues brings us back to the core purpose of education and he agreed with Judy that a central part of the latter should be about preparing citizens to live well with each other in a democracy. This idea is clearly embedded within the rationale for the Northern Ireland Curriculum. One litmus test for this in the Northern Ireland context is the question as to whether we are preparing citizens who will be able to have the debate on the constitutional position of Northern Ireland in a healthy, informed and non-violent way. Given the experience of the Brexit debate and the increasing questions of truth in public conversations, this will be a challenge. The pedagogy of addressing controversial issues is important and very much in line with the revised curriculum and meta-cognition. However, for Sean, there is a question as to whether all teachers are suited to this. He posed his own questions, are there particular qualities an educator requires –and realistically how many teachers display these aptitudes and skills? And what subjects should contribute and can they work together? He emphasised the importance of having young people actively involved in co-creating the ‘safe space’ required to explore issues together but questioned whether those optimal conditions are in fact counter cultural to how schools operate, with their formal structure and set of pre-existing norms of behaviour.

Alan, in his short input, welcomed Judy’s framework and recognised the value of the Structured Academic Controversy approach, with its emphasis on encouraging rational thinking when dealing with disputed issues. However, he wondered if it was helpful to use controversial issues as a generic term and to seek a common approach to teaching which encompasses all issues deemed controversial. Particularly, he suggested that in divided societies, where difficult issues, either in an historical or contemporary context, encroach on individuals’ sense of cultural identity and touch on the legacy of violent conflict, then deep-seated emotions may be aroused which require a distinctive, or adapted, pedagogy.

When discussion was opened up to the “floor” the affective dimension associated with controversy received considerable attention. There was general agreement that this area would be a profitable theme for HTANI investigation and future workshops..